England - Sep18 - Quarry Bank Cotton Mill

|

|

Leaving the Iron Bridge Gorge area, we headed north to the Quarry Bank Cotton Mill which is just south of Manchester.

There are an abundance of interesting things to do in this part of England: Warwick Castle, Beatles stuff in Liverpool, the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester, the Arkwright cotton spinning mill and Masson Mills at Cromford, Matthew Boulton's Soho house near Birmingham.

But we were, as always, limited by time. Since we had to be up at Hadrian's Wall by the end of the day, we only had time to visit one thing down here. So the one place I choose to visit was the Quarry Bank Cotton Mill. It was an outstanding choice!

[Show picture of Grounds]

The entire place was first rate. Quarry Bank was a complete industrial community. We had to walk through the estate to get to the old mill building down by the river which was the museum. The grounds were well kept. Unfortunately it was raining so we couldn't enjoy them as much as we could have on a nice day.

We only had half a day to tour the Mill museum but you could easily spend all day here. In addition to the Mill museum, there was the Workers cottages, Apprentice House, Quarry Bank Houss [owner's house], gardens, many trails including along the River Bollen.

Quarry Bank was an actual cotton mill during the Industrial Revolution. The Mill museum had all the machines, from the spinning wheel, and loom, to Arkwright's spinning machine and Hargreave's jenny, up to early 20th century spinning and weaving machines, with a docent to explain each one, and demonstrate it. You could see and understand how they went from a single person in their cottage spinning thread to a machine that did 16 spools at once, to a machine that did 256 in a factory, powered by waterwheel driven belts. Cotton and textiles figured right at the center of the first phase of the Industrial Revolution and this is a great place to understand how it happened.

Quarry Bank is an example of an early, rural, cotton-spinning mill that was initially dependent on water power. The first mill was built by Samuel Greg and John Massey in 1784. It was a four-storey mill alongside the River Bollin with an attached staircase, counting house and warehouse. It was designed to use water frames which had just come out of patent, and the increased supply of cotton caused by the cessation of the American War of Independence. The water wheel was at the north end of the mill.

The mill was extended in 1796 when it was doubled in length and a fifth floor added. A second wheel was built at the southern end. The 1784 mill ran 2425 spindles, after 1805 with the new wheel it ran 3452 spindles.

|

| |

|

|

There were many components to the Industrial Revolution -- fuel and power, transportation, machinery, the factory -- but perhaps the outstanding feature of the Industrial Revolution was the mechanization of the textile industry, particularly the production of cotton goods.

As the great historian Paul Johnson says: "The reduction in the price of cotton and the increase in its availability from 1780-1850 was one of the best things that ever happened in the world. Sensible people had long dressed in cotton if they could afford it. As Samuel Johnson observed, clothes made from vegetables, like cotton (and linen), could be made truly clean and cool, whereas clothes made from animal materials,like wool and silk, retained an element of grease whatever you did to them. The trouble with cotton was its expense. Up to the point where the cotton industry industrialized itself, to produce a pound of cotton thread took 12-14 man days, one to two for wool. No other article of apparel was so expensive, apart from the best furs. However, it was precisely this labor intensivity of the trade, and the rising demand for its products as western society became wealthier and more fastidious, that acted as a spur to invention and investment. This was the reason cotton figured right at the center of the first phase of the Industrial Revolution.

It was in the 1770s that James Hargreaves's jenny and Richard Arkwright's spinning machine were introduced in England. The consequence was dramatic. In 1765 500,000 pounds of cotton had been spun in England, all of it by hand. By 1784 the total had risen to 12 million, all of it by machine. The next year the new Boulton & Watt steam engines were first used to power the spinning machinery at a factory in Papplewich, Nottinghamshire. That, effectively, was the Big Bang of the Industrial Revolution -- and it was during the 1780s that Britain became the first country in history to achieve self-sustaining economic growth.

More than any other product, cotton was susceptible to cost reductions produced by labor-saving machinery and steam power. By 1812 the cost of cotton yarn ws one-tenth of what it had been even in the 1770s. By the early 1860s, the price of cotton cloth was less than one percent of its price even in 1784, when it was already made by machine. There is no instance in world history of the price of a product in potentially universal demand coming down so fast."

The first textile factories had been water powered, but after James Watt improved the early Newcomen steam engine, steam could be used to power factory machines. This in turn led to increased demand for coal and iron. Every technological development spawned yet another.

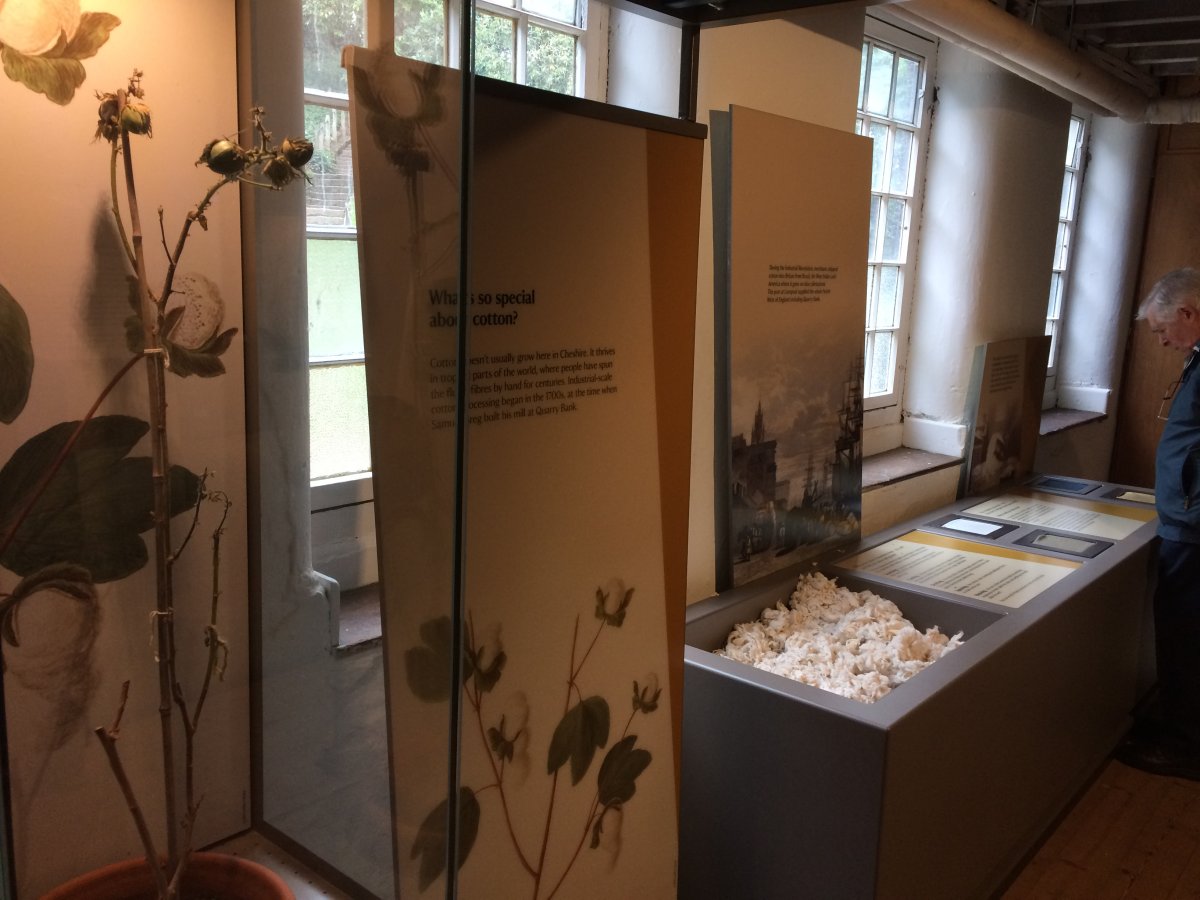

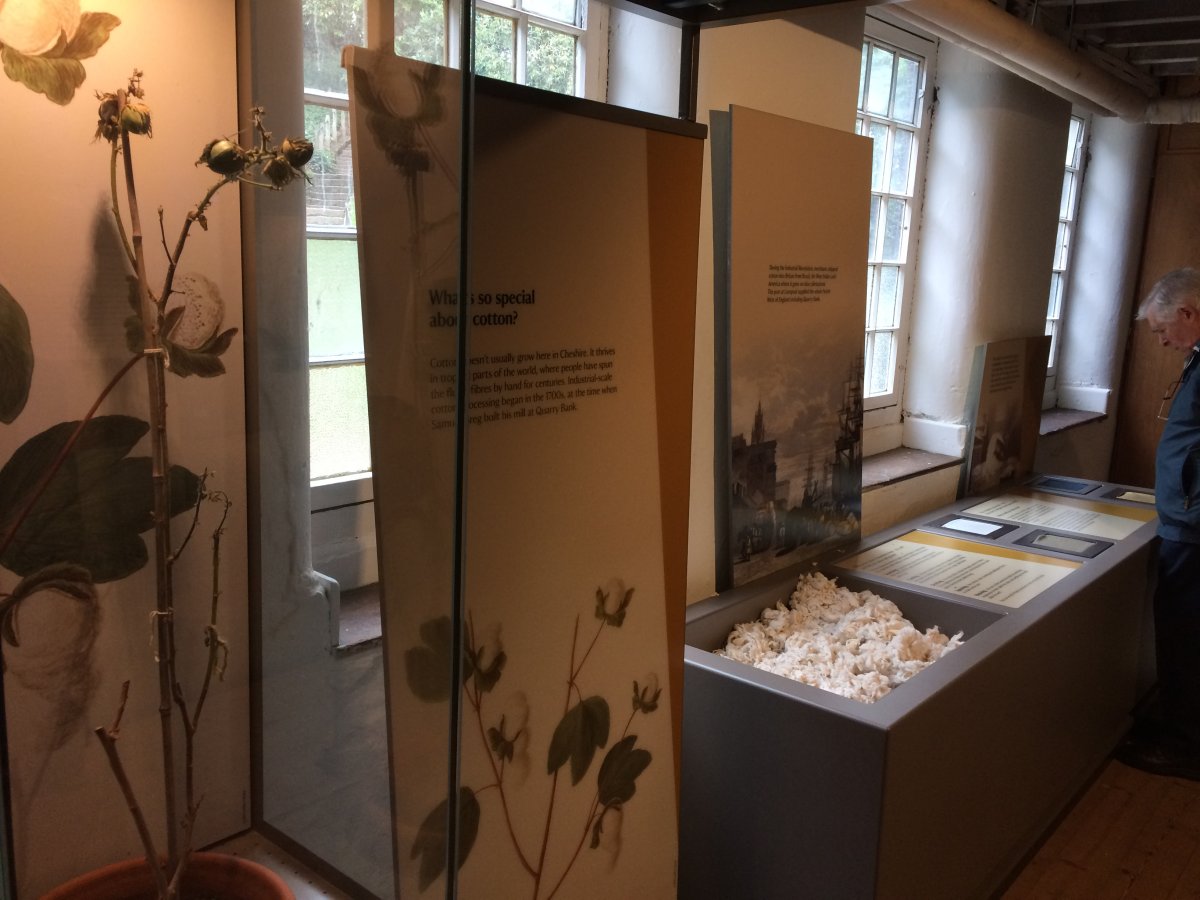

So cotton was big. The museum had a nice exhibit on cotton, as well as the owner, the workforce, and how the machinery was powered .

|

| |

|

|

|

Then there were the early machines with a docent to explain them. The first machine was, of course, the spinning wheel -- visible in the background -- which produced a single strand of thread.

|

| |

|

|

|

Then came this hand-operated machine which produced eight threads at a time. I'm not sure if this is the famous spinning jenny or not.

From Wikipedia: "James Hargreaves was one of three inventors responsible for mechanising spinning. Hargreaves is credited with inventing the spinning jenny in 1764, Richard Arkwright patented the water frame in 1769, and Samuel Crompton combined the two creating the spinning mule in 1779."

Sir Richard Arkwright (23 December 1732 – 3 August 1792) was an English inventor and a leading entrepreneur during the early Industrial Revolution. Although his patents were eventually overturned, he is credited with inventing the spinning frame, which following the transition to water power was renamed the water frame. He also patented a rotary carding engine that transformed raw cotton into cotton lap. But Arkwright's primary achievement was to combine power, machinery, semi-skilled labour and the new raw material of cotton to create mass-produced yarn. His skills of organization made him, more than anyone else, the creator of the modern factory system, especially in his mill at Cromford, Derbyshire. Arkwright became known as the "father of the modern industrial factory system."

|

| |

|

|

|

Which graduated to the Mule: a massive belt-powered machine that produced 128 threads simultaneously. This only the right half of the machine. The entire thing would move on those tracks to the right. Quarry Bank's Mule actually works.

|

| |

|

|

| The center section of the Mule. |

| |

|

|

| Fifty-five pound cotton bales. Much of the cotton during the Industrial Revolution came from America. |

| |

|

|

| There are all sorts of things that must be done to the cotton before it can be spun: carding, combing, roving, etc. Carding is a mechanical process that disentangles, cleans and intermixes fibres to produce a continuous web or sliver suitable for subsequent processing. The museum had numerous machines to do all of this. |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| One of the docents explains this machine. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| An old thread-making machine. This one had a lot of moving parts and was dangerous. |

| |

|

|

| A more modern thread-making machine. |

| |

|

|

|

A modern thread-making machine.

|

| |

|

|

| So you have the thread. Now how do you turn it into cloth? Before the industrial revolution, you would put it in hand-loom like this. A shuttle moves back and forth across -- and in and out of -- the threads. Very time consuming nad labor intensive. |

| |

|

|

| This machine featured a flying shuttle which allowed one person to produce wider cloth. But it is still hand-operated. |

| |

|

|

|

These belt-powered machines do the same thing as the hand-loom, only faster and without human labor (other than someone setting it up, tending the machine, making sure it has thread, and unloading it).

The belts were powered from the water wheel at first, then later by a steam engine.

|

| |

|

|

|

Lots of machines making cotton cloth.

Of course, it was no picnic to work in a factory like this. It was loud. With lots of moving parts, there were many ways to be seriously injured or even killed. The hours were long.

|

| |

|

|

|

The finished product.

|

| |

|

|

|

This is England's most powerful water wheel. It is massive.

At first, the machines were belt-powered by energy from a water wheel like this. But that only worked if the factory was by a river. And there were issues. There might not be enough water in the river to run the water wheel. Steam engines were the answer.

|

| |

|

|

|

The inside of the water wheel.

|

| |

|

|

| The energy from the waterwheel is transferred into useable power using these gears. |

| |

|

|

|

[Add picture of Steam Engine]

Leaving Quarry Bank Mill, we had about a two and a half hour drive up to Hadrian's Wall. It rained fairly hard most of the drive. We stopped here just because of the sign -- the first part of my name -- and ended up eating hot egg/ham sandwiches at a little hiker's cafe.

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|